Emotional engagement differs from behavioural engagement in that students may participate in an activity (behavioural engagement), but may do so without trying their best (emotional engagement). Students’ participation is ideally paired with them caring about what they are doing. This is often referred to as “effort.” Sure, they are doing what you ask, but are they doing the bare minimum? Do you ever get asked, “Is this for marks?” or “How many words does it have to be?” Those questions translate to, “How much effort do I need to put into this?”

Of course, teachers want them to care and do their best effort, but many things can affect how much they care. First, is the topic of personal interest? If it is a general topic for everyone, you can be guaranteed that some will not care. If, however, the topic can be chosen individually by them, it is more difficult not to care. That does not factor in apathy; a response such as, “I can’t think of anything,” may belie an unwillingness to engage. This in itself may be because it would reveal a lack of ability, or that showing enthusiasm for school work is not “cool.” Sometimes students need to be led through the brainstorming process, and once they are on track, they are fine to continue on their own.

Second, students often want to know the relevance of what they are doing: we have all heard students declare, “When am I ever going to have to know Shakespeare again?” or, “I will never need to calculate the surface area of an isosceles triangle when I become a pro wrestler.” If what they are doing seems to connect with their future, they are more willing to put in the effort. Often, what works best is an activity that students don’t see as “work.” Playing a game, or being involved in an activity that allows them to be immersed in it creates high emotional engagement. Having said that, students still want to feel that what they are doing is constructive and helpful for their future (or at least for a higher grade).

This section addresses ways to encourage students’ best efforts. This can be elusive and temporary, at best. What teachers are wanting to tap into is the personal connection that students feel towards the activity. Many experienced educators will have tried one, if not all, of these suggestions. What is key to all of the suggestions and activities is how much students are absorbed in it.

Every elementary teacher knows that getting high emotional engagement is easier when it comes to Mother’s Day and Father’s Day.

How many objects like these are proudly displayed on a shelf from Mother’s Days or Father’s Days past? Students at this level put in effort because they have pride in presenting the objects to their parents, and thus emotional engagement is very high.

Photo by: Dale Sakiyama

In my English 10 class, we read George Orwell’s Animal Farm. As a way to have students really understand the course of events in the novel, I converted the class into “Animal Class.” I assigned each student randomly to one of four groups: Authorities, Hunter/Gatherers, Nurturers, and Builders. Within each group, they had certain responsibilities and tasks to do each day. As each day progressed, I had the Authorities begin to exert more control over the rest of the groups. I warned the students beforehand that while things might get emotional, they must realize that what we were doing was just a class activity. Even though they intellectually knew that this was a class activity, they could not help but react to the Authorities gaining more power and control. In the end, they truly understood the story and also how this allegory applied to the Russian Revolution, because they lived it for about two weeks. In this activity, the emotional engagement was so high that I at times had to intervene so it did not devolve into shouting and physical altercations.

This idea of “living” the novel can be adapted to almost any other lesson, as it is just taking the material and making a real-world application of it. Easier said than done, of course, but most teachers have done this using a number of topics. As a teacher of Social Studies, I took students to the British Columbia legislature buildings to sit in on debate over the Nisga’a Treaty. We were afforded that luxury because we live in the same city, Victoria, as the legislature buildings. Rather than just reading about it, we sat in the gallery to listen to and watch the politicians go through the text. After returning back to the classroom, students then had better context to understand the historical significance of the treaty.

I toyed with the idea of doing the same for William Golding’s Lord of the Flies as I did with Animal Farm, but it was difficult to build in contrasting personalities that would line up with Ralph and Jack in the story. That, and the overall theme of the dark nature of human behaviour did not lend itself well to students enacting the plot!

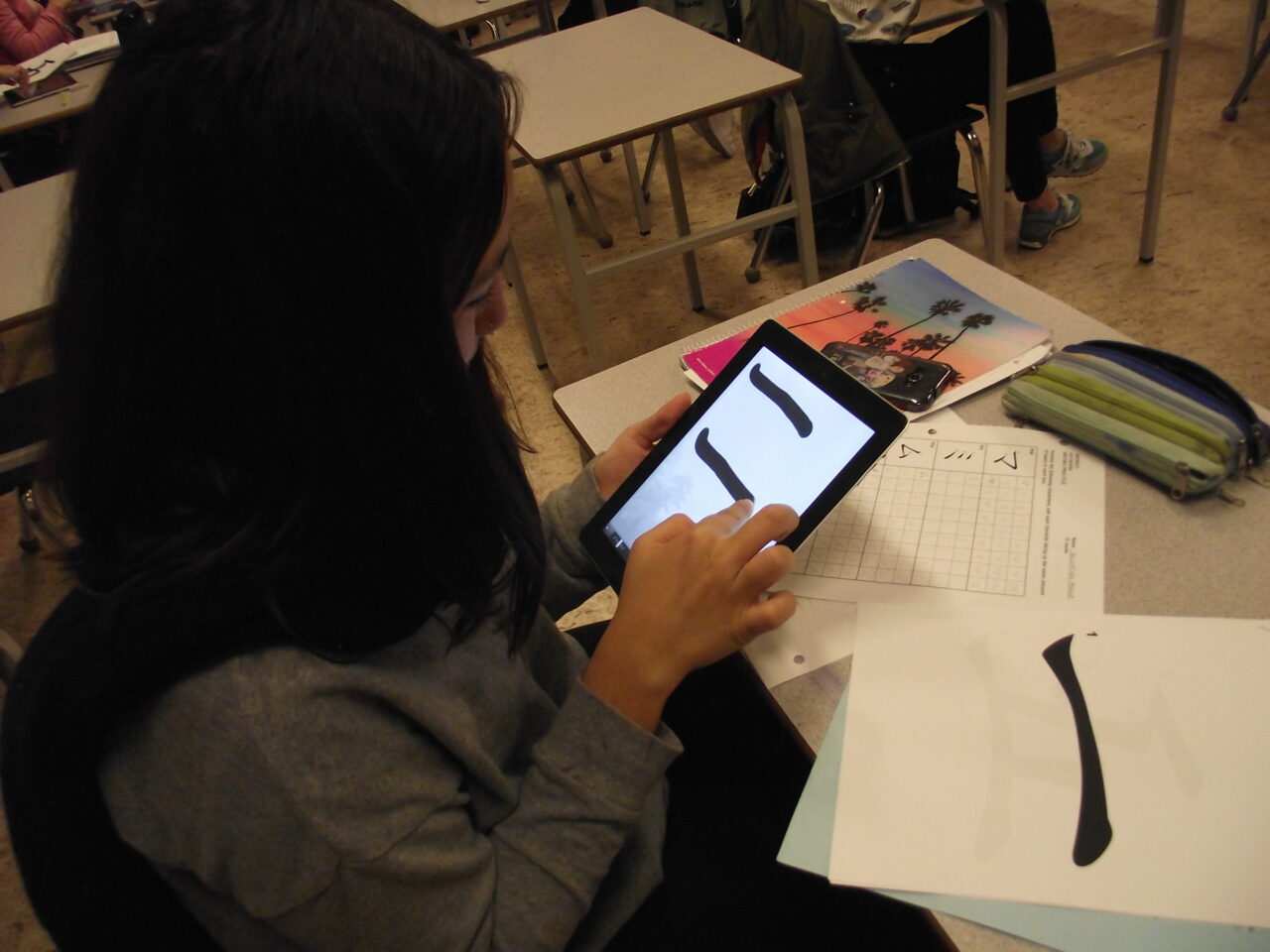

Inquiry Projects generate high emotional engagement because at their core, ideas are directly generated from the student. Rather than a top-down approach from teacher to student, it works from the bottom up; the student deciding, with guidance, which direction the project will take. Trevor MacKenzie has excellent resources to help teachers and students navigate through guided inquiry.

Leave a Reply